- WIADOMOŚCI

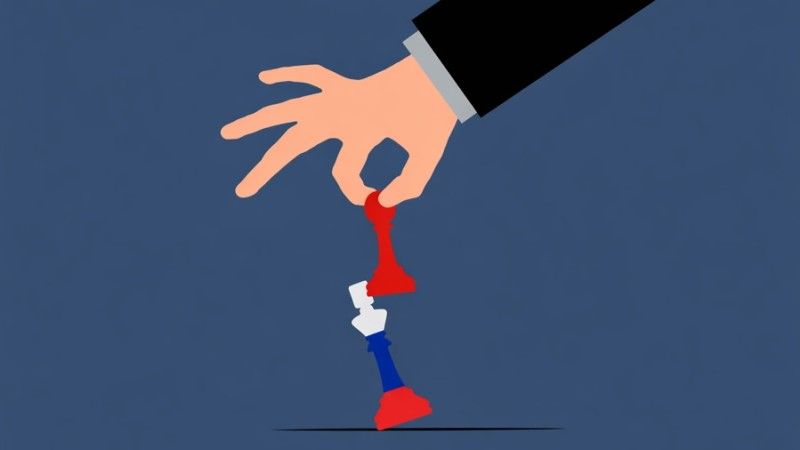

The case for red teaming against hybrid threats

As Russia’s hybrid war intensifies, we need systematic red teaming to expose and fix vulnerabilities before Moscow exploits them first.

We know this pattern all too well by now: Russia launches yet another, more powerful or more creative hybrid attack against NATO countries, which is met with yet another announcement of security measures, programs, and mobilizations until the very next strike comes and the circle repeats.

While learning from one’s own mistakes is often cited as highly effective, it can be equally deadly when applied at a national scale. Relying on retrospection and passive prevention falls short against an innovative, ever-adjusting adversary. Neither in reactive hindsight nor in armchair foresight will we see all the gaps in our security systems that must be closed. In that case, only the next attack will reveal what we have missed.

But what if we stepped into our enemy’s shoes? What if we joined a red team and directed an attack at our own security systems?

What is red teaming?

The red teaming discussed here is a well-established practice in cybersecurity, where independent experts conduct simulated, non-destructive attacks to identify vulnerabilities in targeted systems before real adversaries can exploit them. Widely used in the commercial sector, the approach has recently been adopted by AI companies, which deploy red teams to probe the latest large language models for potential risks by deliberately pushing their safety systems with malicious prompts.

But red teaming traces its roots much further back in the defense world. In Cold War wargaming, the original „red team” played the Soviets against a „blue team” representing Western forces. Over time, the concept moved from the tabletop to the real world, with red teams tasked to test the security of military and other critical installations.

The most famous of them was OP-06D, known as the Red Cell. Created in 1984 and led by former SEAL Team Six commander Richard Marcinko, it conducted simulated terrorist-style attacks against U.S. naval facilities. The team exposed severe security vulnerabilities by penetrating naval bases, planting dummy bombs on aircrafts, and placing simulated charges aboard a nuclear attack submarine.

Following the 1988 Pan Am Flight 103 terrorist attack, red teams were also employed to test airport security. One FAA Red Team reportedly breached airport defenses with „ridiculous ease,” succeeding up to 90% of the time, while a national Red Team study found that over two-thirds of firearms made it past screening. Most egregiously, Logan International Airport was described in a 1999 internal letter as being in a „critical state of non-compliance” with security regulations, a warning that was disregarded by FAA leadership. It suffices to say that two 9/11 flights departed from Logan.

What is hybrid red teaming?

It follows that red teaming can be brutally effective across very different settings. Now it is high time to apply it to one of the most daunting security challenges of our time, hybrid warfare. In other words, it is time for hybrid red teaming: dedicated teams that realistically emulate and build on Russian hybrid tactics to stress-test critical cyber and physical infrastructure, exposing and fixing vulnerabilities before a real attack occurs.

Picture a squadron of highly trained former special forces operators, like Marcinko’s Red Cell, but steeped in Russian hybrid warfare and tasked with a broader range of targets. They would be granted significant operational leeway and institutional independence to conduct controlled attacks, then report after each exercise in a rigorous, structured manner to the appropriate authority and work with it to remedy the vulnerabilities uncovered. Their work, methods, and findings would, of course, remain classified.

As important as the attack’s execution would be its plausibility. The hybrid red teams would have to think as Russians do to devise the most plausible scenarios of hybrid attacks. That would require not only ingenuity and an open mind, but above all a deliberate break from Western preconceptions and adopting Russian strategic culture, escalation logic, and tolerance for risk. To be the red team is not only to act, but also to think as your enemy. Perhaps this would be the biggest challenge: breaking free from the chains of one’s own cognitive biases and limitations.

Then, to have a tangible effect, hybrid red teaming must be a structured, scaled effort, with numerous red teams covering as much critical infrastructure as possible in the shortest feasible time. It should also be internationalized, with national and mixed teams operating across NATO countries and sharing insights. Much could be learned by running the same attack scenarios against similar installations in different states, as well as by having different teams strike the same site in sequence.

While every NATO country should urgently incorporate such a practice into its security system, the frontline states most exposed to Russian hybrid threats on the eastern and northern flanks should make it an immediate priority. Precisely because hybrid pressure is already acute and the risk of escalation is real, the Nordic and Baltic capitals, as well as Warsaw and Bucharest, should move fastest to adopt hybrid red teaming on the shortest feasible timeline.

The real enemy of red teaming

Red teaming attacks can be embarrassingly effective at revealing grievous flaws in security systems, and, paradoxically, that can be the biggest problem. No one likes to have their mistakes and flaws pointed out, and institutions and the people governing them are no exception. Exposing a vulnerability is one thing, fixing it is another.

A telling example of the distance between exposing vulnerabilities and actually fixing them is the case of the FAA’s Red Team in the years before 9/11. In his 2003 testimony before the National Commission on Terrorist Attacks Upon the United States, Bogdan Dzakovic, an aviation security official, accused the FAA of ignoring his Red Team’s warnings. He argued that FAA leadership preferred to maintain a „façade of security” to shield itself from accountability, preserve public confidence and bureaucratic stability, and avoid the economic and operational disruption to the airline industry.

It is not difficult to imagine that some findings from hybrid red team tests could similarly unsettle the leadership of targeted institutions. Fearing the consequences of exposed vulnerabilities, they might opt to bury the results and hope nothing happens. In today’s circumstances, betting that a known weakness will not be exploited sooner or later by Russia is a gamble we cannot afford.

This is why hybrid red teams must be institutionally independent from the organizations they test. Reporting to civilian political leadership rather than sectoral operators is essential, as only political authority can overcome bureaucratic resistance and enforce corrective action across stubborn or risk-averse institutions.

See also

The key to preventing hybrid attacks

As Russia’s hybrid war against the West escalates, the prospect of a first truly devastating or deadly attack is becoming real. The key to prevention does not lie in conventional reactive, often demonstrative measures such as deploying thousands of security personnel to guard railways, energy plants, or undersea cables. This approach is neither sustainable in the medium term nor efficient, as it disperses limited resources across too many potential targets.

Hybrid red teaming, by contrast, offers a way to test critical infrastructure security in practice and in a forgiving environment. It means adopting a proactive defensive posture that exposes vulnerabilities early and raises Russia’s costs in time, effort, and money to breach our systems. In that sense, hybrid red teaming can be instrumental in strengthening Western resilience and deterrence at a moment when both are needed more than ever.